Here's the latest in our video series of tutoring, tutee lessons, and observations.

View additional videos right here.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-hBFCcH7CMY&w=640&h=360]

Here's the latest in our video series of tutoring, tutee lessons, and observations.

View additional videos right here.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-hBFCcH7CMY&w=640&h=360]

We're taking our show on the road this week with an exciting presentation and Camp Show in the Farmington Valley near Hartford, Connecticut. One of the greatest things about Camp Shows is the opportunity to provide "on the ground," free public instruction to a new, diverse audience. Why Connecticut? The parent of a beloved camper invited us, that's why! Read about this parent's observations of her son after Camp Spring Creek in the following press release. If you'd like to host a Camp Show in your area (and see Susie!), just call our office and let us know.

We're taking our show on the road this week with an exciting presentation and Camp Show in the Farmington Valley near Hartford, Connecticut. One of the greatest things about Camp Shows is the opportunity to provide "on the ground," free public instruction to a new, diverse audience. Why Connecticut? The parent of a beloved camper invited us, that's why! Read about this parent's observations of her son after Camp Spring Creek in the following press release. If you'd like to host a Camp Show in your area (and see Susie!), just call our office and let us know.

Dyslexia Awareness & Camp Show

West Hartford, Connecticut – January 21, 2015 – Nationally known dyslexia advocate and camp director Susie van der Vorst presents on early intervention, signs, and solutions.

Camp Spring Creek, located in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, is an academic and recreational camp supporting dyslexic children ages 7 to 14. Invited by a local West Hartford family whose child attended the camp, co-founder and director Susie van der Vorst will discuss early intervention practices, signs, and solutions for parents, teachers, and administrators. van der Vorst will also facilitate a brief discussion of Camp Spring Creek and take questions from the audience. The event is free, open to the public, and welcomes children.

According to van der Vorst, with support, people with dyslexia often lead lives of accomplishment. Some of the most successful people in history had dyslexia, including Winston Churchill, Thomas Edison and Walt Disney. “So many people with dyslexia are misunderstood,” said van der Vorst. “But just look at the wonderful role models we have! Many succeed in spite of their education. Imagine how they’d be if they had been instructed in the ways that they learn best.”

One of the most highly effective methods for such instruction is the Orton-Gillingham approach. It teaches the structure of language using multisensory techniques that lead students to see, hear, and write a concept at the same time. Processing a single concept in many different ways allows dyslexic kids to grasp skills they cannot learn using traditional methods. It’s that approach that drew West Hartford’s Toutain family to the Blue Ridge Mountains, where Winston could attend 1 of only 3 residential camps in the United States accredited by the Academy of Orton-Gillingham Practitioners and Educators.

“We knew dyslexia was a possibility for our son Winston because his father and paternal grandfather have dyslexia. It was important to ius to try and find something that could help, that would also be accredited,” said mother and West Hartford resident, Lesley Toutain. “My husband and I talked with Winston about how being dyslexic doesn’t mean he isn’t smart, simply that he has to find learning strategies that work for him. But I don’t think that really took hold until he was in an environment where all the kids were in the same boat. Camp Spring Creek was an extremely positive experience for him.”

The academic program at Camp Spring Creek includes one-on-one tutoring using the Orton-Gillingham approach, keyboarding and writing classes, one hour of reading aloud each day to camp staff, and one hour of study skills. Optional math remediation or enrichment is available. The activities offered by the program include wood shop, art, swimming, orienteering, and waterskiing. There are also field trips to explore the surrounding Blue Ridge landscape and culture. “We often see students make two to three years worth of progress during a six to eight week session at camp,” said van der Vorst. “Our approach is designed to target a child’s individual strengths and weaknesses and help them excel. But we also recognize the value of keeping kids active throughout the day. These kids can’t learn as well if they’re stuck behind a desk. The learning needs to be hands-on so that they can get multiple senses involved.”

The info session will be held Wednesday, January 21 at 7:00 p.m. at Saint James’s Episcopal Church, 1018 Farmington Avenue, in West Hartford. For more information, call (828) 766-5032 or visit www.campspringcreek.org.

Today’s interview is with inspiring individual David Flink. According to his website, “David, like so many of the kids on whose behalf he serves today, struggled through much of his pre-college education, feeling marginalized by his education as a whole. Although his parents and teachers frequently reassured him that college was in the cards, he would have found that message more actionable, and useful, if it had come from a peer, a person with a learning difference who had finished college. With that in mind, David co-founded Eye to Eye in 1998 while a student at Brown University. Eye to Eye is the only national mentoring movement that is empowering young people with LD by giving them a mentor who shares that experience.” Last month, we recommended David’s book, titled Thinking Differently, and this month we caught up with him by phone for the following interview.

Camp Spring Creek: We’ve seen your video for the Dyslexic Advantage Conference and appreciated your take on life. Can you briefly tell us your dyslexia discovery or diagnosis story?

Today’s interview is with inspiring individual David Flink. According to his website, “David, like so many of the kids on whose behalf he serves today, struggled through much of his pre-college education, feeling marginalized by his education as a whole. Although his parents and teachers frequently reassured him that college was in the cards, he would have found that message more actionable, and useful, if it had come from a peer, a person with a learning difference who had finished college. With that in mind, David co-founded Eye to Eye in 1998 while a student at Brown University. Eye to Eye is the only national mentoring movement that is empowering young people with LD by giving them a mentor who shares that experience.” Last month, we recommended David’s book, titled Thinking Differently, and this month we caught up with him by phone for the following interview.

Camp Spring Creek: We’ve seen your video for the Dyslexic Advantage Conference and appreciated your take on life. Can you briefly tell us your dyslexia discovery or diagnosis story?

David Flink: I was pretty shy as a kid. I had moments of feeling gregarious, especially in things unrelated to academics. If you asked me to pull a quarter out of someone’s ear, you would see a different person than you saw in school. Things really came to a head for me in fifth grade when I went to a Jewish day school, with half the day in English and half the day in Hebrew. I was pulled aside because I was struggling and had all English all day. But it wasn’t that I needed more English, it was how my brain worked. It was not the fault of the teachers, of course, they just didn’t really know about dyslexia in the same ways that we do now. That school actually now has a program for dyslexia with better options. At any rate, at that point in my life I was completely bankrupt in terms of my self-esteem. Thankfully, my parents understood and I was tested and diagnosed.

In some ways, that diagnosis was a relief because I had a word to describe my problem. But in other ways, the words “dyslexia” and “ADHD” and “diagnosis” are not words that inspire a lot of hope for a 5th grader. Because of that, the real “discovery” and optimism happened for me when I was invited to leave the Jewish day school and transferred to the Schenck School in Atlanta. Over the course of two years, I became a square peg with a square hole. My diagnosis finally felt like a discovery and a community, not a condition.

CSC: You're currently touring and speaking due to the success of your book, which we recommended to our readers. Have you faced any surprising challenges on the road that are specific to your dyslexia--perhaps expectations from people managing or organizing events--that have provided a chance for you to creatively problem solve and come at things a different way?

DF: I’ve had some really unusual experiences specific to my dyslexia. If I could point to one that really fleshed out what it means to be a dyslexic author and the goals of Eye to Eye, as well as what it means to be an empowered learner, it would be the interview that I did for a particular radio show. Things were moving so quickly this year that I didn’t have a lot of time to prep. I just sort of showed up. I figured the show would want me to do a reading and I had a passage of my book memorized. I showed up, but they had selected their own parts of the book that created a cohesive message of its own. I didn’t have any of that memorized.

I said I couldn’t do it that way. They said, “What do you mean, you wrote it?”

It turns out, the show was pre-recorded and I had time, so I used my own advocacy skills—the same skills I pinpoint in the book—and I asked for double time to do the recording. Eventually, I memorized their selected passages and read it with the passion that they wanted. It went on the air and it all went over fine. I liked that the experience, in the end, probably taught them a little bit about the scope of all learners and opened them up to being more prepared for hosting dyslexic authors in the future.

CSC: Along the same lines, as a public speaker, is there something you wish other people knew about that experience for someone with dyslexia that doesn’t often come up?

DF: You can’t look at me and know I have ADHD or dyslexia at first glance. In many ways, I think my goal is to normalize that and help underscore that the way I learn is the same for 1 in 5 people in America—literally one of the largest minority groups in the country. I’m hopeful that people who come and hear me speak will understand that I can be an example of the potential for all learners, not just 1 in 5. The key to embracing that potential is unlocking how individuals learn best. Highlighting my two deficits and turning them into strengths, while acknowledging that there are things that will always be hard for me, is still okay. If you embrace the idea that our diversity as learners is a good thing, you can see that it essentially makes us more productive citizens, friends, spouses, brothers, sisters, workers, etc. At our Eye to Eye offices, 80% of our staff has a diagnosed learning difference. We show up with our strengths and our deficits on our sleeves. We can work better that way.

CSC: You seem to have a great sense of humor and welcoming energy. Often times, a gregarious personality is the result of overcoming an inner struggle, private confusion, or loss. Have you always been outgoing, or did you have to teach that to yourself? Did you meet or learn about any role models along the way who informed you about the best way to present yourself?

DF: I think I’m probably naturally a people person, even though I’m more of an introvert. The thing that I taught myself was how to use my story and the story of Eye to Eye as a way to help the world. I like telling stories and I grew up hearing stories. My grandfather was a barber, so if you’ve ever been to an old barber shop, you know that half of it is about how you cut hair and the other half is about what you hear while you’re there. I was always out to do what my grandfather did—the storytelling part—and I had to teach myself that, particularly the public speaking aspect. My general feeling is that you should be whoever you want to be. My ideal evening is often just sitting with my wife and a cup of tea and reading the newspaper quietly.

CSC: Let's talk about this idea that dyslexia is this ability rather than a disability. We agree, and we tell our campers that every single day. Can you give us a real-life example of experiencing your ability in a way that let you think outside the box, creatively respond, or solve a problem when your peers without dyslexia were still "stuck" trying to find their way through?

DF: I like to think that probably happens on some level everyday, because you never grow out of your dyslexia. I would say that best idea that ever came out of my dyslexia and seeing the world differently is Eye to Eye. So many people in this world want to help kids with LD and dyslexia and that’s wonderful, but it’s still not enough. In addition to caring parents and caring teachers, I came to understand that I could play a role that no one else had seen before. I could go meet with a child and tell them what my experience was with LD and listen to their experiences and be a support. In some cases, those kids didn’t have a supportive parent or a place like Camp Spring Creek, so I was the only outlet. In other cases, what I offered enhanced the trajectory for that kid. My ability is my story and only I have that. Seeing that, for me, changed everything.

One of the most exciting things I’ve seen in Eye to Eye is that after our mentees get mentored, they often become mentors. Now, they’ve become so engaged in learning, that many of them are staying in education. That impact is huge. That’s taking a disability and turning it into this ability to think differently.

Today's blog features inspiring individual Sheneen Daniels. Dr. Sheneen Daniels is the Director of the Clinical Division for CReATE, a unique private practice specializing in the provision of evidenced-based evaluations and the implementation of applied clinical research. At CReATE, she manages all clinical, administrative, programmatic, supervision, and training for a team of doctoral-level psychologists, graduate students, and other clinicians. She is a licensed psychologist with over 15 years experience in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of mental health and neurodevelopmental disorders and conditions. Dr. Daniels currently holds a position as Clinical Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with primary duties as Consulting Psychologist to the UNC TEACCH Autism Program (Asheville Center).

Camp Spring Creek: You have conducted thousands of psychological evaluations, many for children with learning differences such as dyslexia. Based on your experience, if there was a message you could give to others about how these children experience the world, what message would that be?

Today's blog features inspiring individual Sheneen Daniels. Dr. Sheneen Daniels is the Director of the Clinical Division for CReATE, a unique private practice specializing in the provision of evidenced-based evaluations and the implementation of applied clinical research. At CReATE, she manages all clinical, administrative, programmatic, supervision, and training for a team of doctoral-level psychologists, graduate students, and other clinicians. She is a licensed psychologist with over 15 years experience in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of mental health and neurodevelopmental disorders and conditions. Dr. Daniels currently holds a position as Clinical Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with primary duties as Consulting Psychologist to the UNC TEACCH Autism Program (Asheville Center).

Camp Spring Creek: You have conducted thousands of psychological evaluations, many for children with learning differences such as dyslexia. Based on your experience, if there was a message you could give to others about how these children experience the world, what message would that be?

Sheneen Daniels: Well, I think the main message would be that children with dyslexia are as unique and diverse as children without dyslexia, and although it is very important to identify dyslexia early in development, I think it is just as important to identify the strengths and gifts of children early as well. I have seen children with dyslexia who are socially gifted, masters at constructing things with their hands, unbelievably musically talented, stellar math students, or athletically gifted; the list goes on and on. Every child has a gift and it is important to identify and build upon these strengths, particularly as you are addressing the child’s challenges with reading and/or school in general. The second most important message is to instill hope with understanding. When parents first receive a diagnosis of dyslexia for their child, sometimes it can be overwhelming and they may believe the diagnosis will be a barrier to their child’s long-term success. The child may have started to feel demoralized as school is a big part of a child’s life and receiving a diagnosis may make them feel as if something is inherently “wrong” with them, rather than understanding that his/her brain may just process information differently. However, with the right intervention, support, and a focus on the child’s strengths, children with dyslexia can be quite successful and the possibilities are truly endless!

CSC: Your career demonstrates an admirable commitment to both research and meeting the needs of people with neurodevelopmental conditions and disorders. Those of us who don't work in the sciences often carry an image of the researcher as an inaccessible scientist, dressed in lab whites, holding a clipboard, and sternly overlooking his/her case studies. Can you tell us a little bit about how you balance the emotion and the science of your work? Do they have to be separate? Or perhaps more keenly stated, how do you negotiate the balance between passionate interest and emotional investment, with the objectivity that clinical research requires?

SD: I firmly believe that psychological testing is both a science and an art. Science in that it requires hypothesis testing, data collection and interpretation, as well as a strong, understanding of evaluation instruments, statistics, and current research. However, it is also an art, because it requires creativity, experience, and compassion in order to translate the science in a way that will be helpful for a particular child or family. It really doesn’t matter how much knowledge you have about statistics or research if you can’t present the information in a way that makes sense for the ones who need to understand it. On the flip side, you can have a lot of compassion but if you do not really understand how the science informs clinical practice, then your ability to help the child or family is limited. Every clinician will talk about cringe-worthy cases early in their career, largely related to their inexperience, self doubt, or refusal to think creatively or flexibly. For me, the cases where I was unable to effectively communicate and instill hope, encourage exploration, and ultimately inspire the family (or child) to move forward, tend to be my greatest regrets. At this point in my career, I can share so many wonderful success stories with parents and children who are receiving the diagnosis for the first time, and this can be very inspiring for them as well.

CSC: There are many barriers to early intervention, not the least of which is simply awareness of the fact that early intervention is important and can yield successful outcomes for children with learning differences. But I'm thinking about some of the families in our neck of the woods--many of whom would struggle to get a day off of work (losing pay) to take their child to Asheville (gas money) for an assessment they can't afford. What options do these families have or where might your refer them?

SD: The child’s school system can be the best place to start, though there admittedly are barriers in this environment as well. There can be long timelines and the school is not required to test a child just because the parents request it, although making the request is the first step and should be done in writing. Parents should remember that they are their child's best advocate and communicating regarding their concerns and/or their child's progress can be instrumental. Regarding private evaluations, insurance and Medicaid do not cover psychological testing solely for educational purposes or to determine if a child has dyslexia specifically. However, if there is also concern about ADHD, Autism Spectrum Disorder or other “medical” disorders, then sometimes the testing can be covered to investigate those conditions. Other diagnoses identified during the evaluation process, including dyslexia, could be documented in the process. Another great resource is a university psychology clinic, where graduate students may administer the tests but are closely supervised by licensed psychologists. Western Carolina University, for example, has a great Psychological Services Clinic and comprehensive evaluations are available for a very low price and may even be discounted based on a family’s ability to pay.

CSC: With your degrees, many areas of research were possible for you. What inspired you to focus your career on neurodevelopmental conditions and disorders, or specifically, learning differences?

SD: I have always really liked math and the sciences always appealed to me; however, I also was drawn to pursuing a discipline where I could make a difference in some way. My first semester of graduate school in clinical psychology included both assessment and statistics courses, which I thought were fascinating, though this was not the case for many in my graduate class! I was intrigued by the variability that I saw in how individuals approached certain tasks and what that might tell us about how their brain processed information or where their strengths might lie. I became especially interested in dyslexia after studying Sally Shaywitz’s work, as she was really able to pinpoint brain functioning through functional MRI’s, and helped to clarify a disorder that was previously misunderstood. And not only did her work bring understanding to dyslexia, but the research also showed that with the right intervention (and early!), individuals could actually modify their brain functioning in ways that could help them to become more fluent readers. I felt that her research brought so much understanding and hope and was able to experience this first hand with a young family member of mine. This particular individual was diagnosed at a young age with a reading disability, though dyslexia was never explained to him. He was quite determined, however, and worked hours on his homework every night for years, though he still struggled. By late high school, however, he was quite discouraged and perceived himself to be not very smart (despite having a superior IQ!). He was conditionally accepted to a local university but had no intention of seeking out support services due to self consciousness and very low expectations for success (he did not believe he would make it past the conditional enrollment period). Around this time, I was nearing the end of my graduate studies and encouraged him to get an updated evaluation with a clinician who had an understanding of dyslexia. The result was truly remarkable. Once he understood that dyslexia meant he had isolated weaknesses in phonemic awareness, spelling, and a slow reading speed -- but that he was quite bright and capable of succeeding in college, his motivation, determination, and expectation for success returned. He subsequently took advantage of support services and accommodations in college and went on to graduate and become a successful professional in the financial field, earning prestigious credentials. This experience highlighted for me, firsthand, the importance of understanding both limitations (i.e., disorders, such as dyslexia) BUT ALSO strengths and how to apply this knowledge towards developing a success-oriented plan for the future.

Here's our latest video from our Homeschool Retreat series. Notice that, at times, the tutoring session can be as much about coaching a student through issues of self-doubt as it is about teaching or practicing an Orton-Gillingham based skill.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3pyA9WZrCWg&w=640&h=360]

Today's interview features inspiring individual Nora S. Newcombe. Dr. Newcombe is Laura H. Carnell Professor of Psychology and James H. Glackin Distinguished Faculty Fellow at Temple University. Her Ph.D. was received in 1976 from Harvard University, where she worked with Jerome Kagan. Her research focuses on spatial cognition and development, as well as the development of autobiographical and episodic memory. A recent emphasis is on understanding the nature, development and malleability of spatial skills that facilitate learning of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). She is currently Principal Investigator of the NSF-funded Spatial Intelligence and Learning Center (SILC) and co-directs the Temple Infant and Child Laboratory (TICL) on Temple’s Ambler Campus and the Research in Spatial Cognition (RISC) Lab on Main Campus. Dr. Newcombe is the author of numerous chapters, articles, and books, including Making Space with Janellen Huttenlocher (published by the MIT Press, 2000). Her work has been recognized by numerous awards and publications. We're delighted to feature her wisdom in this interview.

Camp Spring Creek: We came across your essay published in American Educator titled “Picture This: Increasing Math and Science Learning by Improving Spatial Thinking” and agreed wholeheartedly with your observations. Thank you so much for providing teachers with concrete, age-appropriate ideas about incorporating spatial learning opportunities in their classrooms. We were struck by the idea that “learning styles” (ex. kinesthetic, auditory, visual) are a relative myth, and depend more on what a child is exposed to rather than any innate skills. Can you tell our readership, many of whom were trained under that philosophy of learning styles, a little more about this myth?

Today's interview features inspiring individual Nora S. Newcombe. Dr. Newcombe is Laura H. Carnell Professor of Psychology and James H. Glackin Distinguished Faculty Fellow at Temple University. Her Ph.D. was received in 1976 from Harvard University, where she worked with Jerome Kagan. Her research focuses on spatial cognition and development, as well as the development of autobiographical and episodic memory. A recent emphasis is on understanding the nature, development and malleability of spatial skills that facilitate learning of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). She is currently Principal Investigator of the NSF-funded Spatial Intelligence and Learning Center (SILC) and co-directs the Temple Infant and Child Laboratory (TICL) on Temple’s Ambler Campus and the Research in Spatial Cognition (RISC) Lab on Main Campus. Dr. Newcombe is the author of numerous chapters, articles, and books, including Making Space with Janellen Huttenlocher (published by the MIT Press, 2000). Her work has been recognized by numerous awards and publications. We're delighted to feature her wisdom in this interview.

Camp Spring Creek: We came across your essay published in American Educator titled “Picture This: Increasing Math and Science Learning by Improving Spatial Thinking” and agreed wholeheartedly with your observations. Thank you so much for providing teachers with concrete, age-appropriate ideas about incorporating spatial learning opportunities in their classrooms. We were struck by the idea that “learning styles” (ex. kinesthetic, auditory, visual) are a relative myth, and depend more on what a child is exposed to rather than any innate skills. Can you tell our readership, many of whom were trained under that philosophy of learning styles, a little more about this myth?

Dr. Nora S. Newcombe: Many people feel strongly that they like to learn some ways more than other ways. I think they may be right sometimes about what works for them, but not always. A particularly dangerous idea is that if you don’t like something or think you aren’t good at it, you should avoid it. Now that we know you can improve, it is sensible to say that we should all at least try to be well-rounded. It’s like eating. You may really and truly not like vinegar or artichokes, but you don’t really know until you’ve tried them. You might become an artichoke lover!

CSC: Is there one publication above all others that you might recommend for an enthusiastic education advocate or parent interested in learning differences? We’d like to know about something that isn’t wholly academic, but is still solid in its research and selection of content.

Dr. Newcombe: I would recommend another article in the American Educator. It’s by Dr. Daniel Willingham at the University of Virginia, whose Ask the Cognitive Scientist columns provide a wonderfully accurate and accessible account of what educators should know about cognitive science research. See http://www.aft.org/periodical/american-educator/summer-2005/ask-cognitive-scientist.

CSC: What advice would you give to a new elementary teacher who feels determined to “do it all,” yet likewise overwhelmed by the diverse needs presented by the children in any one given classroom?

Dr. Newcombe: I have never been a classroom teacher, but the teachers I know and admire all seem to me to be good at setting goals for themselves, starting with the basics of simple and solid and engaging classes and sensitive interaction with young children. In the longer run, they work on adding nuances and wrinkles. As with many things, it’s good to keep things simple at first, and proceed day by day.

CSC: We’re curious about your personal interest in education advocacy and spatial learning in particular. What draws you to focus on these things and how have you seen children in your own family struggle or succeed in today’s educational environments?

Dr. Newcombe: My interests are based on my love of science and math. I like to look at maps and graphs and diagrams, and I love visual art too. I just want to spread my passion because I think other people may enjoy (and benefit from) this way of thinking too.

We'd like to offer a round of applause and public note of appreciation to all our grant-funding organizations, partner organizations, trainees, tutors, counselors, staff, parents, and of course--our CAMPERS! Without the team effort from everyone on this list, we could not be where we are today. Where are we? We're in a position to offer slightly more scholarships each year, we're in a position to train local teachers without cost to the teachers themselves, we're in a position to observe and celebrate the accomplishments of our "extended family," we're in a position to expand year-round programming and improve our physical campus, and we're in a position of sincere gratitude to all of you as we look to the future and realize our fullest capabilities are within reach. Slow and steady, we're growing the best ways we know how. Thank YOU for making it possible!

For substantial funding and grants:

Ms. Robyn Oskuie (Endowment)

Dr. Louis Harris (Endowment)

CFWNC (People in Need Grant)

Mitchell Fund (People in Need Grant)

For partner organizations:

Academy of Orton-Gillingham Practitioners and Educators

Augustine Project Winston-Salem

For individual donors:

Philanthropists: Mr. & Mrs. Bill Shattuck, Rainbow Fund, and The True North Foundation.

Benefactors: Triangle Community Foundation

Sponsors: Mr. & Mrs. Tom Brown, Mr. & Mrs. Duane Connell, Mr. & Mrs. Walter Daniels, Mrs. Lori Ferrell, Dr. & Mrs. Bill Sears, Longleaf Foundation, Mr. & Mrs. Samuel S. Polk, Mr. and Mrs. Jeremy Teaford,

Supporters: Mr. Edward Banta, Mr. & Mrs. Charles McClain, Mr. Andrew Oliphant, Mr. & Mrs. Robert Oliphant, Mr. & Mrs. Jonathan Schoolar, Dr. & Mrs. Brian Shaw, Mr. & Mrs. Mike Warren.

Contributors: Mr. Brown & Ms. Rosasco, Ms. Marobeth Ruegg, Mrs. Geradts Cutrone, Ms. Amanda Kyle Williams, Mr. C. Wilson Anderson, Jr., Mr. & Mrs. Dan Blanch, Mr. & Dr. Christy, Mr. Jon Ellenbogen & Ms. Becky Plummer, Mr. & Mrs. Jeff Greene, Dr. & Mrs. David Hoeppner, Mr. & Mrs. Morgen Houchard, Ms. Valerie Imbleau, Mrs. Karen Leopold, Mrs. Theresa Krug, Mr. Thomas Loring, Mr. & Mrs. Brannon Morris, Mr. & Mrs. Joel Plotkin, Ms. Rebecca Morgan, Dr. & Mrs. Anthony Shaw, Mr. & Mrs. Jason Smith, Mr. & Mrs. Robert Tucker, Dr. & Mrs. William Chambers, Dr. & Mrs. Taylor Townsend, Ms. Juanita Greene, Mr. & Mrs. Kevin Schulte, Mr. & Mrs. Matthew Baker, Mr. & Mrs. Ed Anderson, Mr. & Mrs. Roger Burleson, Mr. & Mrs. Charles Tappan, Mr. & Mrs. Scott Ramming, Mr. & Mrs. A D Dreibholz, Mr. Thomas Gilchrist, Mr. & Mrs. Phillip Jackson, Mr. & Mrs. Steve van der Vorst, Mr. & Mrs. Alton Robinson, Mr. & Mrs. Michael Wollam, Mr. and Mrs. Royall Brown.

Friends: Mr. R. Patterson Warlick, Mr. & Mrs. Joe Street, Mr. & Mrs. Frederick Pownall, Mr. & Mrs. Clinton North, Mrs. Nancy Coleman, Mr. & Mrs. David Broshar, E & J Gallo Winery, Ms. Gina Phillips, Mr. & Mrs. Raymond Humphrey, Mr. Paul Eke & Ms. Sonja Hutchins, Mr. & Mrs. James Butts, Mr. Eugene Morris, Mr. & Mrs. Jim O'Donnell, Mr. & Mrs. Ronald Cox, Mr. & Mrs. Roger Vorraber, Mr. John Littleton & Ms. Kate Vogel, Mr. & Mrs. Thor Bueno, Mr. Osaretin Eke.

This video from our Homeschool Retreat features the acronym CLOVER, which stands for the 6 syllable types: closed, consonant LE, open, vowel combo, silent e, and r-controlled. Watch and learn alongside the tutor (who is being observed for certification training hours) as the tutee works on this syllable drill.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WNw-TW15k2A&w=640&h=360]

Here's the next installment in our video series from this fall's Homeschool Retreat. We hope to start using a more sophisticated video camera in 2015, so apologies in advance for the sound quality on this short clip. The visual part of this drill is what is essential, however. Notice how Susie uses gestures and expressions to guide the tutee toward success during this tutoring session: [youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ojdNZCFqb9M]

We recently became aware of Thinking Differently: An Inspiring Guide for parents of Children with Learning Differences written by David Flink. David is both dyslexic and has ADHD, and tells a humorous, informative story in this Dyslexic Advantage video. He wants to change the message about learning differences so that people come to believe that the problem isn't "in" the child or adult who learns differently...rather, the child or adult holds a gift within. "Disability, or this ability," David often says. We're on board!

From the Amazon summary page for David's book: "In Thinking Differently, David Flink, the leader of Eye to Eye—a national mentoring program for students with learning and attention issues—enlarges our understanding of the learning process and offers powerful, innovative strategies for parenting, teaching, and supporting the 20 percent of students with learning disabilities. An outstanding fighter who has helped thousands of children adapt to their specific learning issues, Flink understands the needs and experiences of these children first hand. He, too, has dyslexia and ADHD. Focusing on how to arm students who think and learn differently with essential skills, including meta-cognition and self-advocacy, Flink offers real, hard advice, providing the tools to address specific problems they face—from building self-esteem and reconstructing the learning environment, to getting proper diagnoses and discovering their inner gifts. With his easy, hands-on “Step-by-Step Launchpad to Empowerment,” parents can take immediate steps to improve their children’s lives. Thinking Differently is a brilliant, compassionate work, packed with essential insights and real-world applications indispensable for parents, educators, and other professional involved with children with learning disabilities."

We recently became aware of Thinking Differently: An Inspiring Guide for parents of Children with Learning Differences written by David Flink. David is both dyslexic and has ADHD, and tells a humorous, informative story in this Dyslexic Advantage video. He wants to change the message about learning differences so that people come to believe that the problem isn't "in" the child or adult who learns differently...rather, the child or adult holds a gift within. "Disability, or this ability," David often says. We're on board!

From the Amazon summary page for David's book: "In Thinking Differently, David Flink, the leader of Eye to Eye—a national mentoring program for students with learning and attention issues—enlarges our understanding of the learning process and offers powerful, innovative strategies for parenting, teaching, and supporting the 20 percent of students with learning disabilities. An outstanding fighter who has helped thousands of children adapt to their specific learning issues, Flink understands the needs and experiences of these children first hand. He, too, has dyslexia and ADHD. Focusing on how to arm students who think and learn differently with essential skills, including meta-cognition and self-advocacy, Flink offers real, hard advice, providing the tools to address specific problems they face—from building self-esteem and reconstructing the learning environment, to getting proper diagnoses and discovering their inner gifts. With his easy, hands-on “Step-by-Step Launchpad to Empowerment,” parents can take immediate steps to improve their children’s lives. Thinking Differently is a brilliant, compassionate work, packed with essential insights and real-world applications indispensable for parents, educators, and other professional involved with children with learning disabilities."

Continuing our series of interviews with inspiring individuals, we reached out to Mimi Koehl. Professor Koehl didn't learn she was dyslexic until age 45, when the locks to her lab at UC Berkley were changed from a standard lock and key to a coded keypad. She tried and tried to get into her lab and was routinely locked out. Friend and fellow scientist Jack Horner (also interviewed by Camp Spring Creek, right here), had previously suggested Professor Koehl might be dyslexic. After testing, Dr. Koehl found out that, indeed, she was dyslexic.

Continuing our series of interviews with inspiring individuals, we reached out to Mimi Koehl. Professor Koehl didn't learn she was dyslexic until age 45, when the locks to her lab at UC Berkley were changed from a standard lock and key to a coded keypad. She tried and tried to get into her lab and was routinely locked out. Friend and fellow scientist Jack Horner (also interviewed by Camp Spring Creek, right here), had previously suggested Professor Koehl might be dyslexic. After testing, Dr. Koehl found out that, indeed, she was dyslexic.

Mimi Koehl, a Professor of Integrative Biology at the University of California, Berkeley, earned her Ph.D. in Zoology at Duke University. Professor Koehl is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Her awards include a MacArthur “genius grant,” a Presidential Young Investigator Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the John Martin Award, the Borelli Award, the Rachel Carson Award, and the Muybridge Award. She studies the physics of how organisms interact with their environments, focusing on how microscopic creatures swim and capture food in turbulent water flow, how organisms glide in turbulent wind, how wave-battered marine organisms avoid being washed away, and how olfactory antennae catch odors from water or air moving around them.

Camp Spring Creek: When young college students are asked to choose a path in life, art and science are often perceived at opposite ends of the spectrum. As a young woman, you were pushed to pursue art and education, but quickly learned your passion lay with the sciences. But when you speak about the micro marine organisms that you study, your passion and imagination shine forth--often with vivid, visual descriptions that could easily translate into artwork. Do you still pursue the arts? Can you speak a little bit about the connections you find between these two seemingly opposite fields?

Dr. Koehl: I see two similaritities between what artists and scientists do. One is that we are all careful observers of the world around us. Scientists, however, have invented special instruments that enable us to observe things that we could not see just with our eyes. The other similarity is that both scientists and artists deal with abstractions that capture and simplify the important essence of something. Artists do this with paintings and sculptures, while scientists do this with theories and mathematical equations about how things work. Although both artists and scientists can be passionate about their work, scientists have to follow rules of evidence and hypothesis testing to make sure that the answers to their questions are objective. In contrast, art is very subjective. I have poured all of my creative energy into science, so I no longer do art...but maybe I will pick up art again in the future if I ever retire from doing science.

CSC: When you asked the folks at UC Berkley to provide you with a metal lock and key to your lab, after you proved you were dyslexic, how did they respond?

Dr. Koehl: The Americans with Disabilities Act applies to those of us with "learning disabilities" as well as to people with physical diabilities. Therefore, the university had to give me a metal key to my lab. That key for me is like a wheelchair ramp for people who can't walk.

CSC: You taught yourself many "survival skills" to get through the education system as a young girl. Your father shared many tips and techniques with you as well. Knowing what you know now, are there any everyday habits or "go-to" tools you use to make your work as a scientist and teacher more efficient?

Dr. Koehl: There are many, but I will just share a few simple ones…If you can't read things on a computer screen, print them out and then use the bookmark to help you read them. When writing equations, always leave lots of space around them so you can see what terms are in the numerator or denominator, which things are in parentheses, and which things are exponents. Then, use a different color to write the units for each term of the equation. Then, cancel the units and make sure when you are done that the units for the right side of the equation are the same as for the left side of the equation. If they are not, start over rather than getting muddled by the equation you have written that is wrong. Use lots of colored pens and highlighters and Post-Its to color-code your folders, notes, etc., so that you can find what you are looking for on a page or in a pile of papers without having to re-read them (which can take forever). Do not be messy. Keep all your papers and notes organized so you don't have to try to re-read them whenever you need to find something. Allow yourself LOTS of time to get something done. We dyslexics are very slow if reading is involved in a task. It is easier to understand a scientific principle and then use it to answer questions on an exam (or in real life) than it is to try to memorize all those words in the textbook.

CSC: Has learning about your own dyslexia changed the way you instruct others? If so, please share a specific example with us.

Dr. Koehl: Dyslexics are very good at visualizing things in 3-D and in seeing how they change over time. I have tried to use this ability to design visuals (diagrams, videos) to use in my teaching to explain scientific concepts to my students. I have also found that if I organize my slides, blackboard notes, and handouts so that they are easy to sort out by a dyslexic, then they are also easier to use for normal students as well.

Want more? Check out this creative interview with Mimi at I Was Wondering and her inspiring presentation at Dyslexic Advantage.

We came across this article by Dr. Barbara Moskal via LinkedIn and decided to reach out to her for an interview. We're delighted that she replied! Dr. Barbara M. Moskal is a Professor of Applied Mathematics and Statistics and the Director of the Trefny Institute for Educational Innovation at the Colorado School of Mines. She is also an associate editor for the Journal of Engineering Education. The opinions expressed herein are hers and do not necessarily reflect that of her colleagues or affiliations. Her passions and her work lie in changing the equation for attracting and training students of all ages to STEM.

Camp Spring Creek: In your article about dyslexia and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, & Mathematics), you explained the following: "According to Davis and Braun (2010), in 'The Gift of Dyslexia,' many dyslexic students naturally use three-dimensional reasoning as a technique for problem solving. When dyslexic students encounter a problem solving situation, they naturally change their three-dimensional perspective and examine the problem from various angles without shifting their observation point." But a typical classroom doesn't necessarily engage students with spatial learning opportunities, or the chance to creatively solve something through a student's own best means. How would you advise professionals to create lasting change in our education system that encourages acceptance of creative problem solving?

We came across this article by Dr. Barbara Moskal via LinkedIn and decided to reach out to her for an interview. We're delighted that she replied! Dr. Barbara M. Moskal is a Professor of Applied Mathematics and Statistics and the Director of the Trefny Institute for Educational Innovation at the Colorado School of Mines. She is also an associate editor for the Journal of Engineering Education. The opinions expressed herein are hers and do not necessarily reflect that of her colleagues or affiliations. Her passions and her work lie in changing the equation for attracting and training students of all ages to STEM.

Camp Spring Creek: In your article about dyslexia and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, & Mathematics), you explained the following: "According to Davis and Braun (2010), in 'The Gift of Dyslexia,' many dyslexic students naturally use three-dimensional reasoning as a technique for problem solving. When dyslexic students encounter a problem solving situation, they naturally change their three-dimensional perspective and examine the problem from various angles without shifting their observation point." But a typical classroom doesn't necessarily engage students with spatial learning opportunities, or the chance to creatively solve something through a student's own best means. How would you advise professionals to create lasting change in our education system that encourages acceptance of creative problem solving?

Dr. Moskal: Realistically, scientists and engineers use spatial reasoning everyday. The jobs available in these areas are very rewarding from both a intellectual and financial perspective. All students should have the opportunity to understand science and engineering through the manipulation of their physical world. Not only would this build on the natural abilities that some dyslexic students have but also it is likely to inspire more students’ interests in these lucrative and necessary fields.

Science and engineering were developed using three dimensional reasoning, physical manipulation and experimentation; it is not natural or inspiring to teach these subjects void of these features. If we want students to think like scientists and engineers, then we must allow them to experience science and engineering as the professionals do— through curiosity, experimentation and physical manipulations. Scientists and engineers do use the knowledge of the past and this often requires reading— but this reading is inspired by curiosity and a desire to learn and understand.

In order to implement such a change in the classroom, teachers— especially those who teach science, engineering and mathematics— need to experience science. They need professional development opportunities that allow them to experiment and explore — driven by curiosity and experimentation. What teachers do not need is more text based assignments to give to their students. Science is hands-on. We need to teach it that way.

CSC: Like you, we believe in the importance of early intervention. Can you tell us about one or two organizations or schools that you think are addressing this in compelling, successful ways?

Dr. Moskal: Currently, I am the Director of the Trefny Institute for Educational Innovation at the Colorado School of Mines. Each summer, this institute participates in the Rocky Mountain Camp for Dyslexic Youth (Director: Joyce Bilgrave). We participate in this effort because we believe in the scientific capabilities of these students. Students who struggle to read need to have the opportunity to participate in activities in which they can be successful. Science and engineering offer such activities. For two weeks of this five week camp, we provide hands-on activities that allow students to experience hands-on scientific and engineering learning. Most of the students are excited to come to their one-hour science unit. For many of them, after a challenging morning of reading, science is just plain fun. My graduate students and I have a blast too, because we know science is fun.

CSC: Playing devil's advocate, there are many reasons people might argue in favor of our current education system, which emphasizes literacy above STEM. For example, in order to drive a car and read directions, it's best if you can read. In order to earn a license, in fact, you have to read the laws and pass the test. You don't have to understand mechanical engineering or how your car works in order to drive it from point A to point B...and you don't have to know how the photocopier works that made copies of the test you took, in order to take it. Help us understand the argument in favor of "more STEM" a little bit more, as though you were explaining it to a skeptical parent.

Dr. Moskal: Students do have to learn to read. However, they also need STEM literacy and many of our young dyslexic students can succeed, and succeed at a very high level, in STEM. Yes, please keep teaching our kids to read, but please also let them experience the joy of science, engineering and mathematics. When I was young, children were permitted to have talents in different areas and to develop these talents at different rates. Some students were excellent in English while others were excellent in mathematics. We need to allow all of our children to develop their talents— whether it be English, science, mathematics or the arts. Please stop removing dyslexic students from science, an area in which they may be able to flourish. Mathematical and scientific curiosity can motivate students to read. It is a different type of reading— reading to learn, something scientists and engineers do everyday.

I want to emphasize that reading is very important and our dyslexic students need to learn to read. They also need to experience success and maybe that success will be in STEM. These students aren’t failing, they are failing to learn to read at the pace that society currently demands. Let’s give them school based subjects in which they can succeed (and that are known to be intellectually challenging)— science and mathematics. Based on our experiences at the Rocky Mountain Camp, when given the chance, these students can succeed in STEM.

I recently wrote an article which will appear in Prism, a magazine that is produced by the American Society for Engineering Education. I was asked to write about students with disabilities and I decided to focus on dyslexia. For that article, I decided to seek out colleagues who are scientists and who had been diagnosed with dyslexia. I wanted to offer success stories as examples of what dyslexic students can achieve. The idea to focus on colleagues occurred to me in the morning and I found a match for my article by that afternoon. I hadn’t officially started my search; I just mentioned the article during one of my meetings and an attendee of that meeting spoke to me afterwards. He shared his success and his childhood diagnosis. I can’t help but wonder how many scientists struggled to learn to read, and once they succeeded, forgot about or denied that struggle. It is not a popular thing in the scientific world to admit that learning was once difficult, but I suspect that for many it was.

How many dyslexic children can become successful scientists and engineers if only they were told that they can succeed (and better still— experience that success)? How many children with dyslexia can succeed if they had a role model with the same disability who has succeeded? Let’s set the bar high for all of our children, including those with dyslexia.

CSC: We're really big fans of the Orton-Gillingham approach to learning about the structure of language and find that it is immensely helpful for students with dyslexia--the same students, of course, who more often than not will prove to be very talented in other subject areas, such as STEM. For those of us who don't take naturally to the STEM subject areas, however, what would be the "OG of STEM," so to speak? In other words, for those who show little talent or gifts in the STEM areas (which is different than having a learning difference, we know), what approach or technique might "unlock" these areas?

Dr. Moskal: We all learned through play when we are young; play is instinctual. I play every single day— and it is called science. The OG of science is experimentation and hands-on learning. Unlock the toolkit and allow children to do what they do well— play. Our children need to experience play that is directed to scientific and engineering learning. Play with purpose. Play with enthusiasm. This requires hands-on, physical manipulation and curiosity driven learning. I want all of our children to play.

Last month, we received a very special phone call. Cynia, one of our campers, had exciting news to share. She'd just gotten her report card and saw that she earned straight A's for the first time. What a joy! Cynia called Susie, who says, "I could just hear the excitement in Cynia's voice. She wanted to share her news." We always love hearing from our campers, whether it is to share good news, ask a question, seek advice, or talk about coming back next year.

Last month, we received a very special phone call. Cynia, one of our campers, had exciting news to share. She'd just gotten her report card and saw that she earned straight A's for the first time. What a joy! Cynia called Susie, who says, "I could just hear the excitement in Cynia's voice. She wanted to share her news." We always love hearing from our campers, whether it is to share good news, ask a question, seek advice, or talk about coming back next year.

"More important than the grades Cynia made is the boost the grades gave her self-confidence," says Susie. "We must remember that grades are really extrinsic rewards, but, often they can boost the intrinsic value when you know you have worked hard to achieve something. We are so proud of Cynia and her ability to stick with something until she reaches her goal."

That perseverance is a lifelong skill, and whether the goal is straight A's, learning to rock climb, keeping a promise, or winning a science fair, it takes focus and determination. In celebration of Cynia's achievement, we took a few moments to call Nicole Baker (another inspiring individual interviewed on our blog). “I’ve known Cynia for a number of years and I’ve had the chance most recently to spend time with her on a weekly basis," says Nicole. "She’s always struggled with grades. But when she got her straight A’s report card last month, the first thing she wanted to do was call Susie.”

“Cynia is a firecracker, a spunky spirit for sure," adds Nicole. "She’s one of those kids that has an amazing spark and trajectory. Camp Spring Creek has harnessed that trajectory and guided all Cynia's energy in the best ways. She does have her moments of frustration and getting down on herself. She wants it to come easily. She wants to please everyone and get positive feedback—who doesn’t? All the work she did at Camp Spring Creek gave her the chance to get that and now she’s getting that outside the realm of camp. For example, these recent grades, or when we go to the bookstore now…she can pick out whatever book interests her. She doesn’t have to choose something for an early reader. It’s an exciting time."

Way to go, Cynia! THREE CHEERS!

We're thankful to all our Camp Spring Creek blog readers out there--and that includes tutors, parents, entrepreneurs, education advocates, administrators, campers, counselors, OG enthusiasts, and lovers of all-things-North-Carolina. Since we began actively posting on our blog a year and a half ago, our readership has skyrocketed and we've been able to share interviews with some of today's most creative, successful dyslexics and top educational advocates. We're also increasing our video database, slow and steady (and working on our camera and video editing skills!). We hope you'll spend this weekend with family or friends, or out and about in your community giving thanks for the time we're lucky to have to dedicate to thinking positively about best practices as parents, teachers, and tutors. Whether that means volunteering your tutoring skills for a session, taking extra time to read with your child, or carving out time to research a skill or learning activity you'd like to teach others, we hope it is a restful, meaningful time for all.

We'll be back in December with twice-weekly posts, including more videos in our Homeschool Retreat series. Meantime, if you have feedback to share with us about videos or topics you would like us to address on this blog, please leave your comments here. We'll thank you for it!

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JCc2H6R3MuY&w=640&h=360]

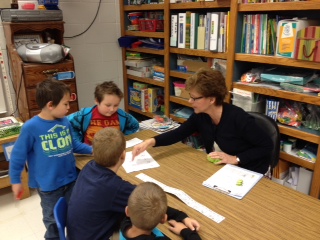

Here's a snapshot from our first Homeschool Retreat, an opportunity that enabled homeschool parents who are also OG tutors to have professional observation by Susie, as well as on-the-spot tips. The tutees were real troopers letting us film them! We also picked apples, baked cookies, and bought pottery--a successful retreat all around! Thursday's post will be another video in this series, with more on the the way...

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mFVezkCAgGA&w=640&h=360]

This excerpt is copyrighted by American Educator and the full article and author info is linked at the bottom of the post. We found this points so helpful, we wanted to include them in summary on our blog: In the elementary school years, teachers need to supplement the kinds of activities appropriate for preschoolers with more focused instruction in spatial thinking. Playful learning of the sort that occurs in preschool can continue to some extent in elementary school; activities such as block building, gesturing, reading spatially challenging books, etc., continue to develop spatial skills in older children too. But as children get older, they can also benefit from more focused lessons. Mathematics is a central subject in which spatial thinking is needed, because space provides a concrete grounding for number ideas, as when we use a number line, use base-10 blocks, or represent multiplication as area. Here are some specific ideas for children in kindergarten through fifth grade:

(Nora S. Newcombe, published in American Educato, copyright 2010) Full article: http://www.aft.org//sites/default/files/periodicals/Newcombe_1.pdf

This content is copyrighted to American Educator and is an excerpt from a longer work written by Nora S. Newcombe. We found it so compelling, we wanted to share, along with one more post on this theme to be released in a few days: Ways to fit spatial learning into the preschool or home learning environment:

objects will appear directly below where they were released, even when they are dropped into a twisting tube with an exit point far away. But, when asked to visualize the path before responding, they do much better. Simply being asked to wait before answering does not help—visualization is key.

objects will appear directly below where they were released, even when they are dropped into a twisting tube with an exit point far away. But, when asked to visualize the path before responding, they do much better. Simply being asked to wait before answering does not help—visualization is key.

Last year's Classroom Educator Course participants, supported by the People in Need grant we received, have officially completed all their classroom and observations hours, meeting all course requirements. Congrats to our local teachers and administrators, who go above and beyond to incorporate OG-principles into their daily work. We appreciate and applaud you!

Here's the second video in our two-part installment on the "drop keep e" spelling pattern.

This is the auditory portion. You can view the visual portion on our YouTube channel linked on the right sidebar.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Da6IoheugdM&w=640&h=360]