Today’s interview features inspiring individual Madalyne Marie. The bio on her website offers a delightful introduction: “Madalyne didn't discover her artistic talent until her freshman year of college, however, she always found ways to cultivate her creativity. She grew up dancing, drumming, canyoneering and river rafting. She always had an interest in learning new things, traveling to new places, and helping others to find strength in their challenges. Her proudest accomplishments include having a piece on exhibit at the Smithsonian…Madalyne lives by the firm belief that good design and creative expression should be applied to everything she does, including cooking, rearranging her furniture, or singing car karaoke at the top of her lungs. She and her husband, Dustin, have been married for five years, live in New York City and have exactly zero children.”

Camp Spring Creek: So much of the design and logo work you have created for companies like Avon, Mark, Coach, and Four & Twenty Sailors involves unique interpretations and layout of letters and symbols. As professional with the dyslexic advantage, we find this especially intriguing. In what ways do you think being dyslexic informs your creative decisions with letters and symbols, specifically?

Today’s interview features inspiring individual Madalyne Marie. The bio on her website offers a delightful introduction: “Madalyne didn't discover her artistic talent until her freshman year of college, however, she always found ways to cultivate her creativity. She grew up dancing, drumming, canyoneering and river rafting. She always had an interest in learning new things, traveling to new places, and helping others to find strength in their challenges. Her proudest accomplishments include having a piece on exhibit at the Smithsonian…Madalyne lives by the firm belief that good design and creative expression should be applied to everything she does, including cooking, rearranging her furniture, or singing car karaoke at the top of her lungs. She and her husband, Dustin, have been married for five years, live in New York City and have exactly zero children.”

Camp Spring Creek: So much of the design and logo work you have created for companies like Avon, Mark, Coach, and Four & Twenty Sailors involves unique interpretations and layout of letters and symbols. As professional with the dyslexic advantage, we find this especially intriguing. In what ways do you think being dyslexic informs your creative decisions with letters and symbols, specifically?

Madalyne Marie: I see words and letters as shapes. This helps me see how the letter-forms interact with each other, as well as the space and the environment that they’re in. That environment might be a website or magazine cover for instance. Being dyslexic also helps me see connections between things and solve visual problems quickly because I can bring my intuitive sense for consistency, evolution, and difference into the brainstorming process. When I work with others, this helps me make the visual connections needed to get the job done, as well as to work efficiently.

CSC: As a graphic designer, your mediums are color and light—two intangible substances. In what ways does being dyslexic inform your ability to manipulate color and light in markedly stunning ways?

MM: Being dyslexic helps me visualize things more clearly and naturally, so I can visualize before I execute ideas. I can see the outcome beforehand and I can see the potential problems as well, so—all around—the work is quicker. For instance, I might decide that I can’t make a background one color and a design feature another color because, in my mind, I can see beforehand that it’s not going to be visually compelling in the way that I want it to be. This is a really positive and empowering tool and I’m still experiencing how useful and important it is, both artistically and professionally.

Growing up, no one shared a message with me about dyslexia that was positive. No one said to me, “I’m dyslexic, I did ok. You’re going to be ok, too.” I’m so passionate about this message now, because there are kids in schools that still think there’s something wrong with them. We need to let them know they’re not attached to a label or an expectation and they’re not attached to shame. They have really positive and empowering tools within themselves, just like I had to discover, as well.

It’s so much easier to label a child “bad” instead of “good.” That kind of thinking isn’t working well for today’s kids. We have to get in on the ground level and reach out to the younger generation. They’re the ones who will change the conversation going forward. If we can get them through school, the more they understand that they’re capable and that they’re needed, the better the world will be.

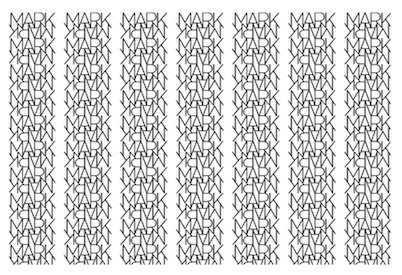

CSC: What can you tell us about the interactive Dyslexic Advantage traveling installation?

MM: It’s a large, interactive installation that combines three components—the experience of someone growing up being dyslexic, juxtaposed with what dyslexia really is, along with an interactive activity that helps someone experience what it could be like for people who are dyslexic. The installation is fairly large and you can pick up letters and interact with it and move things around to complete your experience.

The title of the installation is Dyslexic Advantage, named after the book and research by Brock and Fernette Eide, because it’s such an incredible resource and inspiration to me. They focus on the struggles, but also the achievements of people with dyslexia. That message was important for me to hear.

I made the installation for the capstone of my BFA project at Brigham Young and it was really life changing. The project let everyone know I was dyslexic. I hadn’t really told people before because I didn’t want people to hold me to different standards. I entered the installation into a few exhibition contests, including the Smithsonian, and a few months later I was accepted into their show called “In/finite Earth,” that toured around the world in 2013.

CSC: In brief, what is your dyslexia discovery story? How and when were you identified and in what ways did that influence your life as you moved forward?

MM: I didn’t actually learn what it means to be dyslexic until my senior year of college. I was identified as dyslexic in 2nd grade and was put in special education my entire childhood. My teachers never sat me or my parents down and told us what it all meant. So for many years, I just thought “dyslexic” was a nicer way to say someone was really stupid or unintelligent.

That’s a really hard way to grow up—believing that you’re never going to be as smart as anyone else. I could always tell that the expectations weren’t as high for me and I didn’t like that. When I got to college, I was able to take my first art class. Growing up, I had extra reading and writing classes, so I was never allowed to take art. But in college, at the end of my first semester, my teacher asked me what I was going to major in and I told him Communications. He told me I was crazy if I didn’t major in Art. To make a long story short, I went with art and, in particular, graphic design, and won an award pretty early on. My capstone project was about dyslexia and traveled around the world through the Smithsonian. Finally, I really, truly, started to understand what dyslexia was—and all the positive things it entails.

Today’s interview is with

Today’s interview is with

Today's interview is with

Today's interview is with

Ben’s full story is

Ben’s full story is