Today’s interview continues our conversation with artists who also have dyslexia, and we’re proud to be featuring inspiring individual David Chatt. David has spent the second half of his life stitching tiny bits of glass one to the next, laboring to express himself in a medium that is tedious and time-consuming beyond reason. For his efforts, he has been called a “Visionary,” a “Lunatic,” and a “Beadwork Subversive.” His career was honored with a one-person show at the Bellevue Art Museum in Seattle, Washington, which was commemorated in an accompanying catalog. More recently, he received a North Carolina Artist Fellowship, one of the highest grant awards given by the state and supported by the NEA. View astonishing slideshows of his work here.

Camp Spring Creek: Can you tell us a little about you and your family’s relationship with dysl exia over the years? How has this shaped your experience of the world?

exia over the years? How has this shaped your experience of the world?

David Chatt: I am number five of six children, two girls and four boys. My father and all of the boys had dyslexia, but not to the same degree. Mine was less debilitating comparatively, but it did influence how I grew up. We were none of us very good at sports, and English classes were an exercise in humiliation. We all had similar experiences in school and not being good at these things in an odd way bound us together. Also, I think because we were not those kinds of people, we shared other interests. We built things and made things with our hands. We played games where imagination was more important than coordination.

CSC: The physical process of stitching beads together requires a sophisticated understanding of spatial relationships so that the beaded “skin” fits perfectly over the object you are working with. Superior spatial thinking is a common skill found in people with varying degrees of dyslexia. What can you tell us about your decision-making process as you set out to start stitching these skins?

DC: The technique I employ is a way of building on a three dimensional grid. A loop of four beads can be thought of as a square, one square shares a side with its neighbors and a grid forms. If one can make squares, then one can make cubes…this is how my mind works. I tend to imagine shapes broken down into squares, triangles, pentagons or trapeziums. I have always been good with numbers and math-y kinds of things…spelling no…math yes.

CSC: How does your work as an artist and your family experiences with dyslexia influence your style as a teacher?

DC: I understand that everyone learns differently. I hope and believe that schools are better at dealing with different learning styles but I have certainly been made to feel “less-than” by overworked and under-inspired teachers who wanted nothing more than for this square peg to fit into their dang round hole. As a teacher, I make it a point to let my students know that I understand learning differences and that I count on them to let me know if we need to revisit some instruction with a different approach. Some need to hear the technique described, others need to see directions written out, others need to watch my hands and others still need to have guidance while their hands make the work. I also make it ok to ask me to repeat things because repetition is one of the ways we learn. Being a non-traditional learner has made me a better teacher, and it has also made me understand some of the frustrations my teachers had with me.

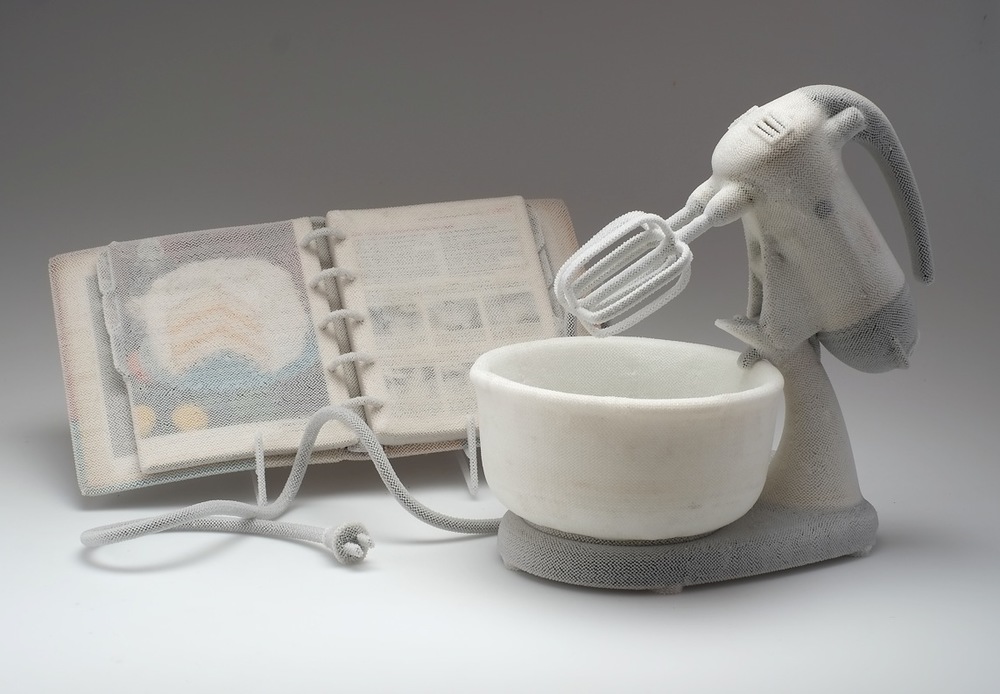

CSC: Your more recent work explores the power of everyday objects in their domestic setting, with an emphasis on narrative, memory, and emotion. In some pieces, you’re effectively taking objects people ignore (for example, we don’t pay attention to our eyeglasses unless a lens pops out) and re-invigorating them with story and a sense of the three-dimensional through your beads and stitching. That’s quite unusual, yet immediately resonate. What’s the lure for you?

DC: Most artists are a wee bit narcissistic. I am always trying to tell my story through the images I choose to engage. My best work finds the place where my personal story touches on something more universal, something that allows my audience to participate. Most of us remember someone who had those glasses. I grew up at a time when women of a certain age wore cat-eye glasses, a strand of pearls and a sweater set. Even if you have only seen that look in old movies, most of us have an association with these items. I seek iconic objects that trigger memory. By covering an object with countless tiny glass beads and meticulous needle-work, I encourage my audience to see these items in a different way. It becomes less that object and more like the place where the object once was, like a memory.

Finding a way to tell your own story is a universal human pursuit. I sometimes wonder if being a kid who was embarrassed about my penmanship and spelling made visual art more of a lure for me. With the advent of the personal computer and spellcheck, I have gradually become less intimidated, and even attracted to the process of writing. This is a surprise to me given my early experiences. In the end, I think it is important to understand that things that are labeled as “disabilities” are often just differences. I am good at this while someone else is good at that. Part of being a creative person is being able to figure out the less obvious ways to get around obstacles. What I have learned from my differences has certainly been more of an advantage than a hinderance.